I was reading a paper by the Google DeepMind team on how they trained Gemini Embedding, a state-of-the-art, unified embedding model. This is the second paper I’ve read this month on training embedding models. Last week, I read about how the Jina embedding model was trained. The Jina embedding paper was thin and lacked details, so I didn’t write about it. This paper is full of insights, so I thought I’d write a short post sharing what I learned.

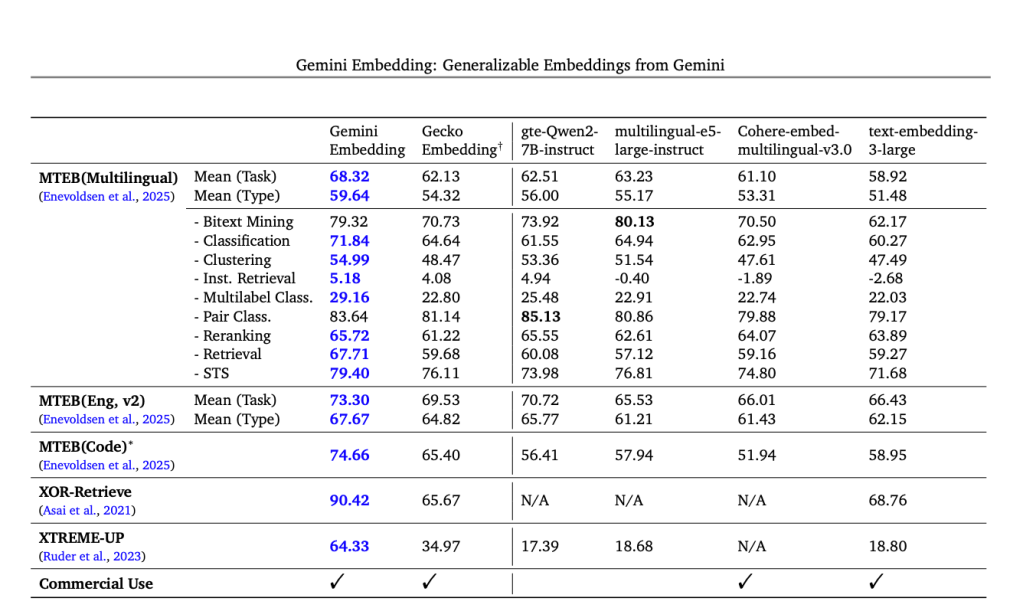

Gemini Embedding achieves state-of-the-art performance across MMTEB’s multilingual, English, and code benchmarks.

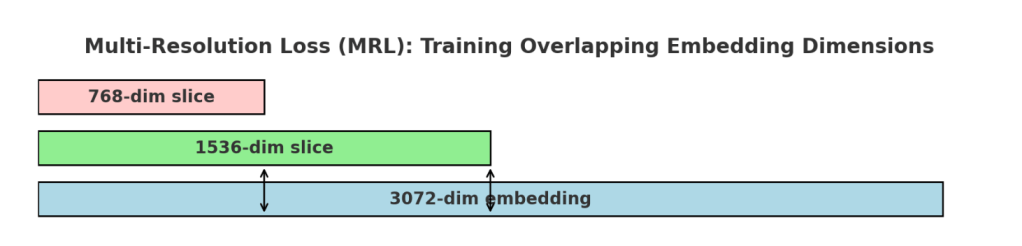

Gemini embeddings use a multi-resolution loss (MRL) so that a single model can produce embeddings of different sizes (768, 1536, 3072). During training, the model applies separate contrastive losses on different sub-portions of the embedding vector, ensuring that both shorter and longer embeddings are well-trained. This provides flexibility: smaller embeddings for efficiency, larger ones for accuracy — all from the same model.

They cite two main reasons why the Gemini Embedding model achieves state-of-the-art performance in benchmarks:

- The Gemini Embedding model is initialized from the weights of the Gemini LLM backbone. They also note that several recent embedding models such as E5-Mistral, SFR-Mistral, BGE-ICL, and NV-Embed have been initialized from the Mistral-7B (Jiang et al., 2023) backbone and then further adapted as embedding models. The same is true for the jina-code-embeddings-0.5b and 1.5b models, as they are built on the Qwen2.5-Coder-0.5B and Qwen2.5-Coder-1.5B backbones.

- The second reason they cite is high-quality datasets. These datasets are synthetically generated using Gemini LLM. They mention: “Leveraging Gemini’s diverse capabilities, we train Gemini Embedding on a comprehensive suite of embedding tasks. To construct a high-quality, heterogeneous training dataset, we employ Gemini for several critical data curation steps: filtering low-quality examples, determining relevant positive and negative passages for retrieval, and generating rich synthetic datasets. This curated dataset facilitates training with a contrastive learning objective, enabling Gemini Embedding to learn robust semantic representations.”

In the paper, they also mention that the Gemini embedding model is trained with a contrastive loss that pulls queries close to their correct targets while pushing away incorrect ones. Negatives are usually sampled from the same batch, and sometimes hard negatives are added to make learning more robust. Each example is also tagged with a task type, which conditions the model to learn embeddings useful across different domains like Q&A or fact-checking.

Each training example also includes a task description such as "question answering" or "fact checking". This string tells the model what kind of relationship between the query and target it should focus on. In effect, it makes the embeddings task-aware, allowing a single embedding model to generalize across multiple use cases.

They also discuss that to train the model they used a two-stage process — Pre-finetuning and Finetuning.

- Pre-finetuning: First, the model is “pre-finetuned” on a large number of potentially noisy (query, target) pairs, omitting the hard-negative term from the loss function. They found it beneficial to use a large batch size, as the primary objective is to adapt the parameters from autoregressive generation to encoding.

- Finetuning: Next, the model is fine-tuned on a large mixture of task-specific datasets containing (query, target, hard negative target) triples. For this phase of training, they found it beneficial to use smaller batch sizes (e.g., less than 1024) and to limit each batch to a single dataset, as distinguishing a given positive target from in-batch targets from the same task provides greater signal than discerning (say) a retrieval target from a classification label.