I spent the second half of 2025 building a voice agent platform for a company that provides IT support services to higher education institutions. The platform is now live and handling calls from students and staff across multiple universities.

We built a multi-tenant system where students call a phone number, speak with an AI agent, and get help with common IT tasks. The three primary use cases we’ve deployed are:

- Password resets — verifying identity and generating new credentials

- FAQ responses — answering common questions about IT services

- Front desk routing — transferring calls to the appropriate department or staff member

The platform is extensible, allowing us to add new use cases with minimal changes to the core system.

Tech Stack

- Backend: Python 3.x, FastAPI, Pipecat, Pipecat Flows

- Speech-to-Text: Deepgram

- LLM: OpenAI GPT-4.1 and GPT-4.1-mini

- Text-to-Speech: Cartesia

- Telephony: Twilio

- Database: PostgreSQL

This stack worked well for a small team of three developers building and iterating quickly.

Architecture Overview

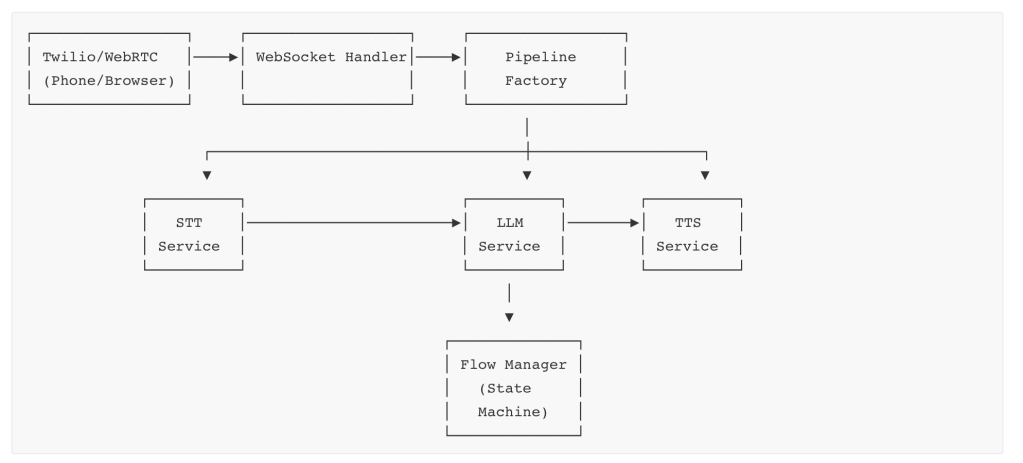

Incoming calls connect via Twilio (or WebRTC for browser-based testing). The WebSocket handler creates a processing pipeline that orchestrates the speech-to-text, LLM, and text-to-speech services. The Flow Manager maintains conversation state, determining which prompts and functions are available at each step.

In this post, I’ll share the principles, best practices, and lessons learned from building this system. While our examples use Pipecat, the concepts apply regardless of your tech stack.

1. State Machines Are Your Friend

The most important architectural decision we made was using state machines for conversation management. Voice conversations are inherently state-driven — you ask for a username, confirm it, verify identity, perform an action, and so on. Each step has specific goals, valid inputs, and available actions.

We used Pipecat Flows, a framework built on top of Pipecat that models conversations as a graph of nodes. Each node represents a conversation state, and transitions between nodes are triggered by function calls.

Each node in a flow defines three things:

- Role messages: The bot’s personality and general instructions (typically set once and shared across nodes)

- Task messages: What the bot should accomplish in this specific state — the immediate goal

- Functions: The actions available in this state, along with their handlers and transition logic

Here’s an example node for confirming a user’s name:

def create_confirm_name_node(flow_manager: FlowManager = None) -> NodeConfig:

return {

"name": "confirm_name",

"task_messages": [

{

"role": get_task_role_for_provider(flow_manager),

"content": dedent(

f"""Confirm the name by repeating it back clearly.

Spell it letter by letter using NATO format "<letter> as in <example word>".

RESPONSE HANDLING:

- If they confirm: Call confirm_name with is_correct=true

- If incorrect: Call confirm_name with is_correct=false

- If they provide a correction: include it in confirmed_name

Wait for explicit confirmation before proceeding."""

),

}

],

"functions": [

confirm_name_func,

transfer_to_agent_func,

],

}

The key insight is that the LLM doesn’t inherently “remember” where it is in a conversation. You have to explicitly tell it what state it’s in and which functions are available. Each node transition resets the task context.

This is actually a feature, not a bug. By scoping each node tightly, you prevent context pollution — where instructions or information from earlier in the conversation leak into later states and cause unexpected behavior. The agent stays focused on exactly what it needs to do right now.

2. Don’t Start with a Drag-and-Drop Flow Builder

Pipecat Flows does offer a visual editor for designing conversation flows, and many voice AI platforms lead with drag-and-drop builders as a key feature. It’s tempting to start there — the visual representation feels intuitive and promises faster iteration.

Resist that temptation, at least initially.

In our experience, every voice agent ends up being different enough that generic, visually-designed flows break down quickly. Once you start handling real calls, you’ll discover edge cases that require:

- Custom validation logic in function handlers

- Dynamic branching based on external API responses

- Subtle prompt adjustments for specific conversation states

- Error handling that varies by context

UI-based flow builders make simple changes easy, but they make complex changes hard. You’ll find yourself fighting the tool instead of solving the problem.

Code-based flows also have a critical advantage: they’re testable. You can write unit tests for individual nodes, integration tests for conversation paths, and regression tests that catch breaking changes before they hit production. With visual builders, testing is often an afterthought — or not possible at all.

Our recommendation: start with code-defined flows that solve your specific use case. Get them working with real users. Once you understand the patterns and edge cases, you can consider moving stable, well-understood flows into a visual editor for non-developers to maintain.

The visual editor is valuable — just not as a starting point.

3. Always Confirm Data by Repeating It Back

In a voice interface, there’s no text field for users to review before submitting. They can’t see what the system heard. This makes confirmation essential — you must repeat back what you captured and get explicit confirmation before proceeding.

This matters because both sides of the conversation are error-prone:

- STT makes mistakes: Speech-to-text engines misinterpret pronunciation, especially with names, email addresses, and alphanumeric strings. Accents, background noise, and mumbling make it worse.

- TTS makes mistakes: Text-to-speech engines can mispronounce individual characters. We’ve seen “Y” pronounced as “E” and “H” swallowed entirely in certain contexts.

Use the NATO Phonetic Alphabet

For any important alphanumeric data — usernames, passwords, confirmation codes — spell it out using the NATO phonetic alphabet: “j as in Juliet, s as in Sierra, m as in Mike…”

This dramatically reduces errors compared to just saying the letters, which often sound similar (“Was that ‘S’ or ‘F’? ‘M’ or ‘N’?”).

Stick to the standard NATO words. Don’t reinvent the wheel by making up your own phonetic mappings. The standard alphabet — Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, and so on — exists because these words were specifically chosen for clarity across accents, languages, and audio conditions. People recognize them. Only deviate if you have a genuine reason, such as a word that your TTS engine consistently mispronounces.

Prefer Numeric Identifiers

Wherever possible, ask for numeric IDs instead of usernames or email addresses. In our case, we ask for the student ID rather than their username or email. STT engines make significantly fewer mistakes transcribing numbers than alphanumeric strings.

Keep Passwords Simple

When generating temporary passwords, use the minimum complexity required by the system. If the policy requires one special character, use exactly one — not three. Fewer special characters means fewer opportunities for TTS mispronunciation and user confusion.

Also add the ability to repeat passwords slowly, character by character. Users will ask for this, and complex passwords often need to be heard more than once.

Ask Only for What You Need

Every piece of information you collect is an opportunity for error. If you don’t strictly need a data point, don’t ask for it. Shorter interactions have fewer failure modes.

4. Invest in Your Admin Portal

This might surprise you: roughly 50% of our development effort goes into the admin portal — not the voice agent itself. Internal tooling, conversation review, configuration management, and debugging interfaces are just as important as the call-handling code.

Most teams underinvest here. When I interview developers who’ve built voice agents, I ask what they learned from real interactions. Most struggle to answer, or admit their teams spent very little time on admin tooling. Without good internal tools, you’re flying blind.

Turn-Level Conversation Analysis

The biggest unlock is viewing conversations at the turn level. A turn is a single back-and-forth exchange: the user speaks, the system processes, the bot responds. Each turn can involve multiple steps — STT transcription, LLM inference, function calls, TTS generation.

For every turn, capture:

- Timestamps: When did the user start speaking? Stop speaking? When did the bot start and stop?

- Transcripts: What did STT hear? What did the LLM generate?

- Function calls: Which functions were invoked, with what parameters, and what did they return?

- Latency breakdown: How long did each step take?

- Token counts: How many tokens were used for this turn and cumulatively for the conversation?

Once you have turn-level demarcation, debugging becomes dramatically easier. Instead of listening to a 3-minute call trying to find the problem, you can jump directly to the turn where things went wrong.

Turn-Level Replay and Testing

Beyond just viewing turns, build the ability to replay individual turns directly from the admin portal. For any turn in a past conversation, let users re-run that exact turn — same input, same context — and see what the LLM produces.

This is invaluable for debugging because:

- LLMs are non-deterministic: Running the same turn multiple times shows you whether the model behaves consistently or produces different outputs

- Isolated testing: You can test a specific problematic turn without replaying the entire conversation

- Prompt iteration: When refining prompts, you can re-run historical turns to see if your changes improve behavior

This feature alone has saved us countless hours of debugging. Instead of guessing why a call went wrong, we can replay the exact turn and watch the LLM’s behavior.

Call Playback and Recording

Store call recordings and make them easy to play back alongside the turn-level data. Being able to hear exactly what the user said while seeing what STT transcribed is invaluable for diagnosing issues.

Configuration Management

Expose configuration settings through the admin portal rather than hardcoding them. For each voice agent, we expose settings like:

- Model selection (which LLM, STT, and TTS to use)

- Idle timeout configuration

- Transfer routing rules

- Prompt variations

This lets you make adjustments without code deployments and enables non-engineers to tune agent behavior.

Permissions and Access Control

Invest in a proper RBAC (Role-Based Access Control) model from the start. You’ll have different audiences — developers debugging issues, operations staff monitoring performance, customer admins reviewing their own calls — and they need different levels of access. Retrofitting permissions later is painful.

5. Transfer to Human Should Always Be the Fallback

No matter how good your voice agent is, some calls need a human. The user might have an edge case you haven’t handled, they might be frustrated with the bot, or they might simply prefer talking to a person. Always give them that option.

Make Transfer Explicitly Available

At every stage of the conversation, users should be able to request a human agent. Include transfer_to_agent as an available function in every node of your flow, and make sure your prompts acknowledge this option when appropriate.

However, don’t transfer automatically — always tell the user what’s happening and confirm before initiating the transfer. A sudden “Please hold while I transfer you” is jarring. Instead: “I’m not able to help with that, but I can transfer you to a support agent. Would you like me to do that?”

Transfer Routing Gets Complicated

What seems like a simple “transfer to human” action quickly becomes complex in production:

- Time of day: Is the help desk open? Different routing for business hours vs. after hours.

- Day of week: Weekday vs. weekend staffing may differ.

- Holidays: Public holidays and university breaks need special handling.

- Team availability: Should the call go to an onsite team or an offsite/outsourced team?

- Department routing: Does the call need to go to a specific department based on the issue?

- Queue management: What if all agents are busy?

This routing logic has to live somewhere. We handle it in our backend, but you could also integrate with your contact center’s existing routing rules. The key is deciding upfront where this logic belongs and keeping it maintainable.

Handle Unanswered Transfers

What happens when no one picks up? You need to plan for this:

- Timeout handling: How long do you wait before considering the transfer failed?

- Voicemail option: Can you route to voicemail or a callback request system?

- Return to bot: Should the caller return to the voice agent with a message like “I wasn’t able to reach an agent. Can I help you with something else, or would you like to leave a message?”

- After-hours messaging: If transferring outside business hours, inform the user before attempting.

Don’t leave users in limbo. Every transfer path needs a defined outcome.

Log Everything

Log all transfer-related events so you can track calls end-to-end:

- Transfer requested (and why — user-initiated vs. bot-initiated)

- Transfer destination

- Transfer outcome (answered, voicemail, failed, timeout)

- Time spent waiting

- Post-transfer call duration (if you have visibility)

This data helps you understand where calls are going and whether transfers are being resolved successfully.

6. Function Calling Is Where Most Things Go Wrong

If there’s one area where voice agents fail unpredictably, it’s function calling. The LLM needs to recognize when to call a function, which function to call, and what parameters to pass — and it needs to do this reliably across varied user inputs. When it doesn’t, calls break in ways that look like hallucinations but are actually function-calling failures.

Be Explicit About Available Functions

Don’t assume the LLM will figure out when to use functions based on their names and descriptions alone. In your prompts, explicitly state which functions are available and when to use them:

"""AVAILABLE FUNCTIONS:

- confirm_name: Call this after the user confirms or denies their name is correct

- is_correct=true: User confirmed the name

- is_correct=false: User said the name is wrong

- transfer_to_agent: Call this if user explicitly requests a human agent

IMPORTANT: Wait for explicit user confirmation before calling any function.

Do not proceed without calling one of these functions."""

The more explicit you are, the more reliably the LLM will invoke functions correctly.

Don’t Rely on the LLM for Validation

A common mistake is letting the LLM handle validation — checking username formats, verifying password length, validating email addresses. Don’t do this. LLMs are inconsistent at applying rules precisely.

Instead, let the LLM collect the input and do all validation in your function handlers:

async def handle_username(args: FlowArgs):

username = args["username"]

# Validate in code, not in the prompt

if len(username) < 3:

return {"error": "Username must be at least 3 characters"}

if not username.isalnum():

return {"error": "Username can only contain letters and numbers"}

# Proceed with validated input

return await lookup_user(username)

Validation in code is deterministic, testable, and won’t randomly fail on the 50th call.

Recognize Function-Calling Failures

When the LLM fails to invoke a function it should have, it doesn’t error out — it generates a response instead. This looks like a hallucination, but it’s actually a function-calling failure.

For example, instead of calling confirm_name(is_correct=true), the LLM might say: “Great, I’ve confirmed your name. Let me proceed with the next step.” It sounds right, but no function was called, so no state transition happens. The conversation gets stuck or behaves unexpectedly.

The fix is almost always in the prompt. Common causes:

- Function descriptions are ambiguous

- The prompt doesn’t clearly instruct when to call the function

- Too many functions are available, confusing the model

- The prompt allows the LLM to “narrate” actions instead of calling functions

Function Calls Are Testable

The upside of function-based architectures is testability. Unlike free-form LLM responses, function calls are structured and deterministic in shape. You can:

- Unit test handlers: Test each function handler with known inputs and expected outputs

- Test function invocation: Create test cases with sample user inputs and verify the LLM calls the correct function with correct parameters

- Regression testing: Build a suite of historical turns and verify that prompt changes don’t break previously-working function calls

This testability is one of the strongest arguments for structuring your voice agent around explicit function calls rather than free-form responses.

7. API Failures and Timeouts

Your voice agent will call backend APIs to actually do things — look up users, verify identity, reset passwords, check account status, create tickets. These APIs will fail. Design for this from the start.

Unlike a web app where you can show an error message and let the user retry, a voice call has no visual feedback. Silence is death. If an API hangs for 5 seconds, the user thinks the call dropped. If it fails without graceful handling, the conversation breaks in confusing ways.

Fill the Silence

When calling backend APIs that may take a moment, tell the user what’s happening before making the call. Use Pipecat’s frame queue to speak while the operation runs:

async def handle_password_reset(args: FlowArgs, flow_manager: FlowManager):

# Tell user what's happening BEFORE the API call

await flow_manager.task.queue_frame(

TTSSpeakFrame("Let me look up your account. One moment please.")

)

# Now make the API call - user hears the message while waiting

try:

result = await call_with_retry(lambda: lookup_account(args["student_id"]))

return {"success": True, "account": result}

except APIError as e:

return {"success": False, "error": str(e)}

This prevents awkward silence and reassures the user that the system is working. Even a brief “One moment” makes a significant difference in perceived responsiveness.

Expect Failures

Every backend API call should assume failure is possible:

- Downstream services: Your identity provider, Active Directory, ticketing system, or database may be slow or unavailable

- Network issues: Transient connectivity problems between services

- Rate limits: Backend systems may throttle requests during peak load

- Timeouts: Services that normally respond in 200ms might occasionally take 10 seconds

Don’t treat failures as exceptional. They’re normal operating conditions in production.

Implement Retries

For transient failures, retries often succeed. We’ve found that two retries are sufficient in most cases — if something fails three times, it’s unlikely to succeed on the fourth attempt, and you’re just adding latency.

async def call_with_retry(func, max_retries=2):

for attempt in range(max_retries + 1):

try:

return await func()

except TransientError as e:

if attempt == max_retries:

raise

await asyncio.sleep(0.1 * (attempt + 1)) # Brief backoff

Be selective about what you retry. Retry on timeouts and 5xx errors. Don’t retry on 4xx errors — those won’t fix themselves.

Communicate Clearly with Users

When an API call fails, tell the user what’s happening in plain language. Avoid technical jargon or vague statements.

Bad: “An error occurred. Please try again.”

Bad: Silence followed by the bot continuing as if nothing happened

Good: “I’m having trouble looking up your account right now. Let me try again.”

Good: “Our system is running slowly at the moment. Please bear with me.”

If retries fail, offer a path forward: “I’m not able to complete this right now. Would you like me to transfer you to a support agent?”

Set Appropriate Timeouts

Every backend API call needs a timeout. Without one, a hanging service will freeze your entire conversation. We typically use 5-10 seconds depending on the expected complexity of the operation.

Tune these based on your p99 latencies. The timeout should be long enough to accommodate normal slow responses but short enough to fail fast when things are broken.

Log Requests and Responses

Log every backend API call with:

- Request payload (or a summary for large payloads)

- Response payload

- Latency

- Status code or error type

- Retry attempts

This is essential for debugging production issues. When a call fails, you need to see exactly what was sent and what came back — not just that an error occurred.

Apply Distributed Systems Principles

Building a production voice agent means building a distributed system. The same principles apply:

- Timeouts everywhere: Never wait indefinitely for any backend call

- Circuit breakers: If a service fails repeatedly, stop calling it temporarily rather than piling up failures

- Graceful degradation: If a non-critical service is down, continue with reduced functionality rather than failing entirely

- Idempotency: Retried operations shouldn’t cause duplicate side effects (don’t reset a password twice)

8. Understanding the Latency Stack

Voice AI has an unforgiving latency budget. Industry data from contact centers indicates that customers hang up 40% more frequently when voice agents take longer than one second to respond. Unlike chat interfaces where users tolerate a few seconds of “typing…” indicators, phone conversations have deeply ingrained timing expectations. Silence feels broken.

Defining Latency in Voice Agents

Latency in voice agents isn’t a single number — it’s the sum of multiple sequential steps. A “turn” consists of:

- User finishes speaking → Voice Activity Detection (VAD) determines they’re done

- Audio transmission → Speech travels to your server

- Speech-to-Text → Audio is transcribed

- LLM inference → Model generates a response

- Text-to-Speech → Response is converted to audio

- Audio transmission → Speech travels back to the user

- Playback begins → User hears the first syllable

Each step adds latency, and they’re mostly sequential — you can’t start TTS until you have text from the LLM.

The Latency Budget

Here’s a typical breakdown of where time goes in a voice agent turn:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Latency Budget (~800-1200ms) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ VAD + endpointing: ~100-200ms │

│ Network (to server): ~20-50ms │

│ STT (Speech-to-Text): ~100-300ms │

│ LLM inference: ~300-600ms │

│ TTS (Text-to-Speech): ~100-200ms │

│ Network (to client): ~20-50ms │

│ Audio playback start: ~20ms │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The LLM is typically the largest contributor, but don’t ignore the others — they add up quickly.

Our Latency Numbers

Model selection significantly impacts latency. Our stack — Deepgram for STT, OpenAI for LLM, and Cartesia for TTS — has worked well. Here are our p95 latencies in production:

| Component | p95 Latency |

|---|---|

| STT (Deepgram) | 41ms |

| TTS (Cartesia) | 11ms |

| LLM (GPT-4.1-mini) | 1.5 seconds |

| LLM (GPT-4.1) | 2.5 seconds |

As you can see, our STT and TTS are fast — the LLM dominates. This is why we use GPT-4.1-mini for most conversational turns and only invoke the full GPT-4.1 when we need its additional capability.

Measure Obsessively

You can’t optimize what you don’t measure. We built a custom TurnLatencyObserver that extends Pipecat’s TurnTrackingObserver and UserBotLatencyLogObserver to capture timing for every turn:

- When the user started speaking

- When the user stopped speaking (VAD endpoint)

- When STT returned the transcript

- When the LLM started streaming

- When the LLM finished

- When TTS started

- When the first audio byte was sent to the user

This granular data lets us identify exactly where latency spikes are occurring and whether the problem is our code, our prompts, or an external service.

Optimization Strategies

A few techniques that help:

- Streaming responses: Don’t wait for the complete LLM response before starting TTS. Stream tokens to TTS as they arrive.

- Shorter prompts: Fewer tokens in, fewer tokens out, faster inference.

- Model selection: Use smaller models (like GPT-4.1-mini) for simple turns; reserve larger models for complex reasoning.

- Connection reuse: Keep persistent connections to STT, LLM, and TTS services to avoid handshake overhead.

- Geographic proximity: Deploy your servers close to both your users and your AI service providers.

The goal isn’t just a good average latency — it’s a good p95 and p99. Users remember the worst experiences.

9. Spelling Things Out Is Surprisingly Complex

When your voice agent needs to communicate alphanumeric strings — passwords, usernames, confirmation codes — you can’t just pass them to the TTS engine and hope for the best. If you send “jsmith1234” directly, most TTS engines will try to pronounce it as a word, producing something unintelligible.

Even if you format it as individual characters, you’ll hit problems:

- Letters that sound alike: “S” vs “F”, “M” vs “N”, “B” vs “D”

- Characters that get mispronounced: We found Cartesia pronouncing “Y” as “E” and swallowing “H” in certain contexts

- No pauses between characters: Users can’t keep up if the letters run together

- Case ambiguity: Is that uppercase or lowercase?

The NATO Phonetic Alphabet Approach

We solved this by spelling out every character using the NATO phonetic alphabet, with explicit case indication and pauses between characters. Here’s our implementation using SSML (Speech Synthesis Markup Language):

def spell_with_phonetics(text: str, break_time: int = 1) -> str:

nato = {

'a': "Alpha", 'b': "Bravo", 'c': "Charlie", 'd': "Delta",

'e': "Echo", 'f': "Foxtrot", 'g': "Golf", 'h': "Hotel",

'i': "India", 'j': "Juliet", 'k': "Kilo", 'l': "Lima",

'm': "Mike", 'n': "November", 'o': "Oscar", 'p': "Papa",

'q': "Quebec", 'r': "Romeo", 's': "Sierra", 't': "Tango",

'u': "Uniform", 'v': "Victor", 'w': "Whiskey", 'x': "X-ray",

'y': "Yankee", 'z': "Zulu"

}

symbols = {

'!': "exclamation mark", '@': "at symbol", '#': "hash",

'$': "dollar sign", '_': "underscore", '-': "hyphen",

'.': "dot", '/': "forward slash"

}

parts = []

for ch in text:

if ch.isalpha():

case = "lowercase" if ch.islower() else "capital"

phonetic = nato[ch.lower()]

parts.append(

f'{case} <spell>{ch}</spell> as in {phonetic} '

f'<break time="{break_time}s"/>'

)

elif ch.isdigit():

parts.append(f'number {ch} <break time="{break_time}s"/>')

elif ch in symbols:

parts.append(f'{symbols[ch]} <break time="{break_time}s"/>')

return " ".join(parts)

For input "Js5@", this produces:

capital <spell>J</spell> as in Juliet <break time="1s"/>

lowercase <spell>s</spell> as in Sierra <break time="1s"/>

number 5 <break time="1s"/>

at symbol <break time="1s"/>

The <spell> SSML tag tells the TTS engine to pronounce the character as a letter rather than trying to interpret it. The <break> tag adds a pause between characters, giving users time to write each one down.

TTS Engine Quirks

Each TTS engine has its own quirks that you’ll need to work around:

- Mispronunciations: As mentioned, Cartesia mispronounced certain letters in specific contexts. Test every letter and number systematically.

- Unexpected interpretations: Cartesia pronounced quotation marks (

") as “inches” — perfectly logical for the engine, completely confusing for users. We built aQuotationRemovalTextFilter(extending Pipecat’sBaseTextFilter) to strip them from output before sending to TTS. - SSML support varies: Not all engines support all SSML tags. Test your markup with your specific provider.

Allow Users to Request Repetition

Even with careful spelling, users will sometimes miss characters. Always offer to repeat:

- “Would you like me to repeat that?”

- “I can spell that again more slowly if you’d like.”

For passwords especially, expect to spell them at least twice. Build this into your conversation flow rather than treating it as an edge case.

10. People Say the Same Thing in Different Ways

Users don’t follow a script. When asked to provide information verbally, they’ll use whatever format feels natural to them. Your voice agent needs to handle all of it.

The OTP Problem

One-time passwords are a perfect example. Ask someone to read a 6-digit code, and you’ll hear:

- “Five five two two two two” (digit by digit)

- “Double five, triple two” (grouped by repetition)

- “Fifty-five, twenty-two, twenty-two” (as number pairs)

- “Five five, two two, two two” (with pauses that STT might interpret as separators)

- “M as in Mike, zero two three zero four four” (with a prefix)

The STT engine will transcribe these differently. “Double five” might come through as “double 5”, “double five”, or “55” depending on the engine and context.

Normalize Aggressively

The solution is aggressive normalization. Strip everything except the characters you care about:

def normalize_otp(otp: str) -> str:

"""

Normalize OTP by extracting only the numeric part.

Handles various OTP formats:

- Full format: "M-023044" -> "023044"

- With hyphens: "P-023-044" -> "023044"

- Spoken: "double 5 triple 2" -> handled by STT + this

"""

if not otp:

return ""

return "".join(char for char in otp if char.isdigit())

This simple function handles most cases because STT engines typically convert spoken numbers to digits. “Double five” becomes “55” in the transcript, and we just extract the digits.

Beyond OTPs

The same principle applies to other data types:

- Phone numbers: “(555) 123-4567”, “555-123-4567”, “5551234567”, “five five five, one two three, four five six seven”

- Dates: “January 5th”, “1/5”, “the fifth of January”, “01-05”

- Times: “3 PM”, “3 o’clock”, “fifteen hundred”, “3 in the afternoon”

- Amounts: “fifty dollars”, “$50”, “50 bucks”, “fifty”

For each data type you collect, build a normalizer that extracts the canonical form regardless of how the user expressed it.

Normalize First, Validate Second

A good pattern is:

- Receive the raw STT transcript

- Normalize to a canonical format

- Validate that the normalized result meets your requirements (length, format, etc.)

- Confirm with the user by reading back the normalized value

Don’t try to validate before normalizing — “double five triple two” won’t pass a “must be 6 digits” check, but “552222” will.

Handle Ambiguity Explicitly

Some phrases are genuinely ambiguous. “Fifteen” could be “15” or “50” depending on accent and audio quality. When normalization produces an unexpected result, confirm with the user rather than assuming:

- “I heard five five two two two two. Is that correct?”

- “Just to confirm, that’s the number 552222?”

Confirmation is cheap. Failed transactions are expensive.

11. Prompt Engineering Matters More Than You Think

Voice prompts are fundamentally different from chat prompts. In a chat interface, users can skim a long response, scroll back to re-read, and take their time parsing information. In a voice interface, users hear your response exactly once, at the speed you deliver it, with no way to scroll back.

This changes everything about how you write prompts.

Keep Responses Short

We cap responses at 30-50 words. Anything longer and users lose track of what was said.

Keep responses around 30 words, and no longer than 50 words.

Do not include unnecessary preamble or filler phrases.

Get to the point immediately.

This constraint forces the LLM to be concise. Without it, models tend to produce helpful but verbose responses that work in chat but are exhausting to listen to.

Use Conversational Language

Written text and spoken text are different. Instruct the LLM to write the way people talk:

Use contractions (I'm, you're, we'll, let's) to sound natural.

Avoid formal or stiff language.

Write the way a friendly support agent would speak.

“I am going to look up your account” sounds robotic. “I’ll look up your account” sounds human.

Document Functions Explicitly

As discussed in Section 6, the LLM needs explicit instructions about available functions. Don’t rely on function names and descriptions alone — tell the model exactly when to use each function:

AVAILABLE FUNCTIONS:

- confirm_name: Call this AFTER the user confirms or denies their name

- is_correct=true if they confirmed

- is_correct=false if they said it's wrong

- transfer_to_agent: Call this if the user explicitly asks for a human

IMPORTANT: Wait for explicit user confirmation before calling any function.

Do not assume confirmation from ambiguous responses.

Add Message Variations

If your agent says “Great, I found your account” the exact same way every time, it sounds robotic. Users notice repetition, especially if they call multiple times.

Build in randomized variations for common responses:

ACCOUNT_FOUND_MESSAGES = [

"Great, I found your account.",

"Perfect, I've located your account.",

"Got it, I found you in the system.",

]

await flow_manager.task.queue_frame(

TTSSpeakFrame(random.choice(ACCOUNT_FOUND_MESSAGES))

)

This small touch makes the agent feel more natural without changing the underlying logic.

Handle Off-Topic Gracefully

Users will ask random questions — about the weather, about unrelated services, or just to test the bot. Your agent needs to redirect these without breaking the conversation flow.

We inject off-topic handling instructions dynamically based on the current conversation state:

def get_off_topic_handling_text(node_context: str) -> str:

base_message = "I can only help with password resets today."

context_redirections = {

"name_collection": "What's your name?",

"username_collection": "Let's get your username.",

"verification": "Let's continue with verification.",

}

redirect_text = context_redirections.get(

node_context,

"Let's get back to your password reset."

)

return f"""HANDLING OFF-TOPIC REQUESTS:

- Politely redirect using variations like:

- "{base_message} {redirect_text}"

- "I'm here just for password resets. {redirect_text}"

- Attempt redirection up to 2-3 times before escalating to a human

- Stay friendly and helpful throughout

- Maintain a casual, conversational tone"""

The key is redirecting back to the current task without being dismissive. “I can’t help with that” feels like a dead end. “I’m here for password resets today — what’s your username?” keeps the conversation moving.

Iterate Based on Real Calls

Prompt engineering for voice agents is empirical. You won’t get it right the first time. Build a workflow for:

- Listening to calls where something went wrong

- Identifying the prompt gap — what instruction was missing or unclear?

- Updating the prompt with more specific guidance

- Testing the change using turn replay (Section 4) to verify the fix works

- Monitoring to ensure the change doesn’t break other cases

The prompts you deploy on day one will look nothing like the prompts you have after a month of production calls.

Conclusion

Building a voice AI demo is easy. Building a production voice agent that reliably resolves real calls is hard.

The demo shows the happy path — a cooperative user, clear audio, no edge cases. Production shows you everything else: accents the STT struggles with, users who say “um” for five seconds, API timeouts at the worst moment, and a hundred ways to spell the same username.

Start Small, Learn Fast

The pattern we’ve seen work: start with low-risk use cases where the alternative is no service at all. After-hours support is ideal — if the voice agent can’t help, callers would have gotten voicemail anyway. This gives you room to learn the technology and build confidence before expanding to higher-stakes workflows.

Our Top Recommendations

Based on everything we learned:

- Start with the state machine. Get your conversation flows right before worrying about latency optimization. A fast agent that takes users in circles is worse than a slightly slower one that resolves their issue.

- Test with real phone calls early. Browser-based testing is convenient, but it doesn’t surface the audio quality issues, network hiccups, and user behaviors you’ll encounter on actual phone calls. Get on the phone as soon as possible.

- Instrument everything. You will have prompt issues. You will have function-calling failures. You will have edge cases you never imagined. Good observability — especially turn-level logging and replay — lets you find and fix problems fast.

- Plan for graceful degradation. Voice calls can’t show error pages. When something fails, the user needs a clear message and a path forward. That path should always include the option to talk to a human.

Voice Is Different

Building voice agents is fundamentally different from building chatbots:

- Real-time streaming: No buffering. Every millisecond of latency is felt.

- Unreliable channels: Audio cuts out, users go silent mid-sentence, networks drop.

- No visual fallback: You can’t show a diagram or a list. Everything must be spoken clearly.

- State complexity: Phone calls have more states than chat — hold, transfer, conference, voicemail, DTMF input.

- Higher stakes: Users expect phone calls to work. A broken chatbot is annoying; a broken phone call is infuriating.

Final Thoughts

The Pipecat ecosystem gave us a solid foundation. Deepgram, Cartesia, and OpenAI each performed well for their respective roles. But the framework and services are just the starting point. The real work — and the real differentiation — is in the details: idle handling, pronunciation quirks, transfer logic, error recovery, and the dozens of small decisions that determine whether your agent feels helpful or frustrating.

We spent the second half of 2025 learning these lessons. Hopefully this post saves you some of the same mistakes.

If you’re building voice agents and want to exchange notes, I’d love to hear from you.

Discover more from Shekhar Gulati

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.